How to Avoid this Fatal Sandbox Error

I think one of the big mistakes people make when trying to run a sandbox campaign is taking the idea of "You're free to explore" so seriously that you avoid anything that might nudge them in a certain direction. But isn't it the nature of choice that you prefer the option you chose over all the alternatives? If players have no reason for wanting to go in one direction over others, it's not much of a choice.

So look for ways to break up the symmetry of the sandbox. These don't necessarily have to be big, elaborate plots. Though a good sandbox ought to have NPCs hatching plots. When things go wrong, it could generate a mystery to solve. Or it might just land in the PCs laps.

But it doesn't have to be that plot-heavy. When I was experimenting with Appendix A (random dungeon design), I started tossing in a chance for a roll on Appendix I (dungeon dressing), particularly in empty rooms and at corridor intersections.

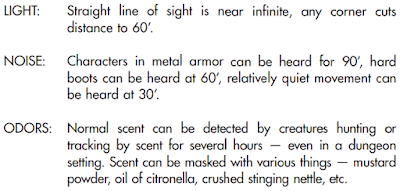

The dungeon dressing tables include things such as smell, breeze and direction, and clarity of the air. They include sights, like a broken arrow on the ground, and sounds, like the sound of footsteps walking away. It was especially neat when a sound came up, because as I was creating/mapping, this told me I should create/map that direction first.

Just dropping in some of these at random gets the players thinking. Be willing to improvise. If they hear the sound of muffled screams, they have to be coming from someone. Decide who's screaming, what or who is muffling said screams, where they are, and what's going on. Now you have an adventure.

Here's another thing I do. Part of sandbox play is loving random encounters. A good wandering monster table is part of the description and characteristics of that area of the sandbox. When an encounter is generated, roll a d4. 1 = the players arrived early, 2 = play it normal, 3 = PCs arrived late, and 4 = PC's arrived way late.

So if it's an encounter with bandits, a 1 means the PCs arrive as the bandits are setting up their ambush and can surprise attack the bandits or else just move on and warn others. A 2 means play the encounter as normal. Bandits try to rob PCs. 3 means the PCs arrive at the encounter late, the bandits have already attacked a traveling merchant, and if they hurry, they can thwart the bandits. 4 means PCs arrived way late, they might find an abandoned and looted wagon with a dead body or two. Or maybe a lone stranger with no weapons, wealth, or even shoes, who had just gotten robbed.

Finally, take some "prep" time, preferably immediately after each session, to ask yourself how what has transpired in the session might affect the game world. So they succeeded at killing, capturing, or driving off the bandits. Does a new gang move into the area? Do two new gangs try to move in simultaneously causing a turf war? Or maybe the thievery does stop and more merchants are willing to travel the roads creating fierce competition among existing ones.

So look for ways to break up the symmetry of the sandbox. These don't necessarily have to be big, elaborate plots. Though a good sandbox ought to have NPCs hatching plots. When things go wrong, it could generate a mystery to solve. Or it might just land in the PCs laps.

But it doesn't have to be that plot-heavy. When I was experimenting with Appendix A (random dungeon design), I started tossing in a chance for a roll on Appendix I (dungeon dressing), particularly in empty rooms and at corridor intersections.

The dungeon dressing tables include things such as smell, breeze and direction, and clarity of the air. They include sights, like a broken arrow on the ground, and sounds, like the sound of footsteps walking away. It was especially neat when a sound came up, because as I was creating/mapping, this told me I should create/map that direction first.

Just dropping in some of these at random gets the players thinking. Be willing to improvise. If they hear the sound of muffled screams, they have to be coming from someone. Decide who's screaming, what or who is muffling said screams, where they are, and what's going on. Now you have an adventure.

Here's another thing I do. Part of sandbox play is loving random encounters. A good wandering monster table is part of the description and characteristics of that area of the sandbox. When an encounter is generated, roll a d4. 1 = the players arrived early, 2 = play it normal, 3 = PCs arrived late, and 4 = PC's arrived way late.

So if it's an encounter with bandits, a 1 means the PCs arrive as the bandits are setting up their ambush and can surprise attack the bandits or else just move on and warn others. A 2 means play the encounter as normal. Bandits try to rob PCs. 3 means the PCs arrive at the encounter late, the bandits have already attacked a traveling merchant, and if they hurry, they can thwart the bandits. 4 means PCs arrived way late, they might find an abandoned and looted wagon with a dead body or two. Or maybe a lone stranger with no weapons, wealth, or even shoes, who had just gotten robbed.

Finally, take some "prep" time, preferably immediately after each session, to ask yourself how what has transpired in the session might affect the game world. So they succeeded at killing, capturing, or driving off the bandits. Does a new gang move into the area? Do two new gangs try to move in simultaneously causing a turf war? Or maybe the thievery does stop and more merchants are willing to travel the roads creating fierce competition among existing ones.

Comments

Post a Comment